On Swift Nudes and Flying Friars

by TheunKarelse (first published > http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=4390 ) a reading companion for the field guide to flying saints

In researching the lives of the saints, I recently came across some interesting parallels with Marcel Duchamp's use of the female nude. The unreachable 'Brides' that appear in many of his works are thought to be sources of desire and creativity, which drive the 'Bachelors' into a frenzy. But this passion turns out to be one of reason and almost scientifically meticulous attention, and as emotionally detached as a game of chess. What are we to make of this?

During my research I came across a conversation between the Russian monks Gregory Rasputin and Iliodor.(1) Rasputin said he felt great energy and spiritual inspiration from being around women. He said Saints and church Elders would undress prostitutes to gaze at them, but without any physical contact. What occurred was a strange combination of scoptophilia (sexual gazing) and angelophany (meeting angels). Rasputin himself practiced this method, visiting St. Petersburg brothels and women at the royal palace. By managing one's lust, the soul could become so refined as to rise into the air despite the weight of the body, and Rasputin cited the miracles of Jesus as examples of this soul levitation.

Figure 1. St. Joseph of Cupertino

In the history of the Catholic Church there are 200 noted cases of male and female Saints who had the spectacular ability to fly. The most impressive is St. Joseph of Cupertino, Italy (Fig. 1), a Franciscan friar born on June 17, 1603, whose ecstatic flights earned him the epithet 'Flying Friar.'(2) As a boy he was sickly, absent-minded, nervous, hot-tempered and unable, because of his states of ecstasy, to stick to a job. Often he would stop in mid-sentence, forgetting the conversation he was engaged in; and suddenly kneel or to stand stock still at awkward moments. Joseph was sent to Grotella in 1628, where for ten years he performed many miracles, to the wonder of the people in the surrounding countryside. Because he drew so many large crowds, his desperate superiors sent him from convent to convent, hidden from the world and basically imprisoned. His life was threatened when he was denounced to the Inquisition at Naples, but after three 'examinations' he was freed After that, Joseph was sent to Pope Urban the 8th. When he saw the Holy Father, he flew into the air and remained there until the Pope ordered him down. Hordes of Pilgrims followed Joseph. The Spanish ambassador and his cohorts saw him take off and fly over their heads to the high altar, uttering his usual shrill cry. After twice seeing Joseph in ecstasy, the Duke of Brunswick became a Catholic. The monks tried to distract him with needles and burning embers, but they could not divert him from his trance. He would be caught by a vision that fixed him like a statue. At dinner he was known to fly around holding his plate; or, when working outdoors, suddenly hover in a tree, caught in a state of amazement at the world. When Pope Innocent the 10th ordered him to retire, he spent the rest of his life in seclusion.

In the life of Joseph, no mention is made of desire as an agent for his gift of flight. But the lives of Saints have been dominated by desire and repentance ever since St. Anthony the hermit, who can be seen flying in a stunning picture by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Temptation of St. Anthony, Oil on wood. The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

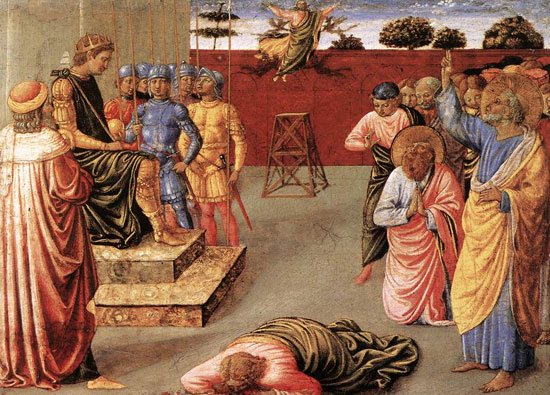

The origins of the sacred 'muse' appear from the court magician of Emperor Nero, Simon Magus,(3) who has been erased from Catholic history and is remembered only as 'the Father of all Heretics.' Born in Gitta in the first century A.D. this man, the founder of Gnosticism, battled mightily with St Peter, we are told, in an attempt to overthrow Christianity. He had the power to heal, to turn stones into bread, travel through the air, stand unharmed in fire, change shape, become invisible, move objects, and open locks without touching them. Simon, a Faustian figure, is thus a scientist turned magician. In trying to imitate Simon's gift of flight, St. Peter broke his legs. But many accounts, such as this picture by Benozzo Gozzoli (Fig. 3) tell of Simon's tragic fall.

Figure 3. Benozzo Gozzoli, Fall of Simon Magus, 1461-62, Tempera on panel. Royal Collection, Hampton Court.

Nearly all records concerning the Magus have been destroyed. Simon explained the purpose of the Magus (which was misunderstood by the followers of Jesus), as enlightenment. The consciousness of the magician is at one with 'Nous,' or Reason. Adam's knowledge before the Fall is a true and perfect knowledge of nature, a Natural Magic. Such Reason must be combined with 'Epinoia,' or Thought. Simon found this aspect of enlightenment in a relationship with a prostitute from Tyre, in whom Simon claimed to see the spirit of God. This is reminiscent of the frenzy of Duchamp's 'Bachelor' as caused by his 'Bride.'

In early Christianity, as in most religions, there were sacred prostitutes whom the community held in high esteem. These women were manifestations of direct physical interaction with the divine. The Gnostics believed the spirit of God had been trapped in matter, especially in humans, during the creation of the world. Thought can be trapped in form, and the images created can be abused by corrupt men. This abuse must be redeemed by 'Nous.'

Some Gnostics claim Jesus rescued Mary from a life of prostitution, as Simon did Helena. And that that the Church felt ill at ease with this similarity, so Simon was erased from history.

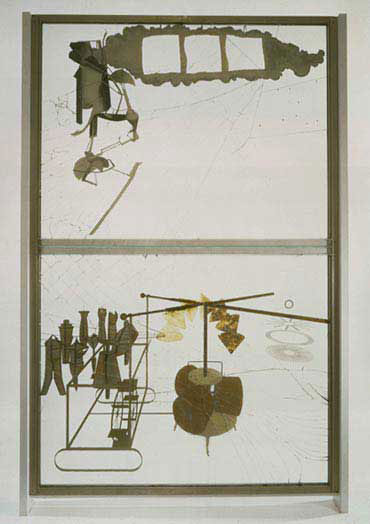

In Duchamp's Large Glass, (Fig. 4) a nude female levitates. This elevated muse creates a frenzy among the 'bachelors' that physically remain below. And as long as their admiration of the nude remains a visual one, they will not rise, just like the church Elders. They can only leave their mundane lives when they can see in her the beauty of Creation.

Figure 4. Marcel Duchamp, Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even [a.k.a. The Large Glass], 1915-23, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

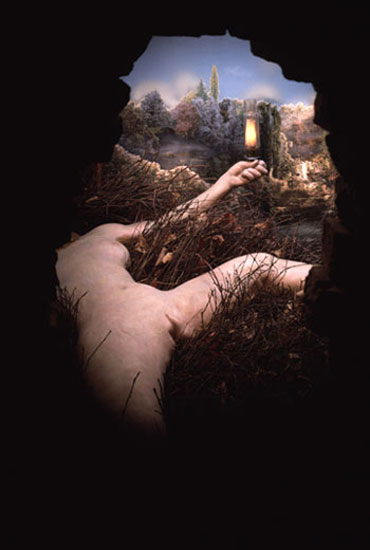

In Duchamp's last work, Etant donn's (Fig. 5), the bride seems to have fallen, like Simon, and has crashed into a tree. Why this happened is a mystery, but perhaps she fell because her 'bachelor' is no longer there.

Figure 5. Marcel Duchamp, Given: 1. The Waterfall / 2.The Illuminating Gas (interior), 1946-1966. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

– Theun Karelse, 2003, Amsterdam.

- 'Rasputin the Last Word', Edvard Radzinsky

- New Catholic Encyclopaedia, various books on Saints and web sources via the Google directory of Saints

- New Catholic Encyclopaedia, various books on Saints and web sources via Google