Table of Contents

Alternate Reality Games Tutorial

Based on the ARG Tutorial by Adrian Hon and Matt Wieteska1)

The prehistory of alternate reality games

Creating an alternate reality in fiction isn’t a new concept. Books, radio-plays, games, theatre improvisations or fortune-telling all include elements that are used in Alternate Reality Games (ARGs). ARGs’ unique approach to storytelling and alternate reality is their straddling of the online and the physical worlds and including the players’ daily life as elements in the story. ARGs smear stories across transmedia contents and technologies – from tweets and blogs, live events and physical puzzles to social networks and mobile apps. Although the media might be contemporary, some storytelling devices used in ARGs can be traced back several decades and even centuries, pointing to the continued inspiration and excitement that alternate realities offer for their readers, players, and inhabitants.

War of the Worlds2) is an example of an alternate reality that was written as fiction, but was perceived as real. This well-known radio play consisted of fake news stories about an alien invasion, causing a mass panic among its listeners when it was first broadcast in 1938. It gets remade every few years and still tricks people into thinking that it’s real.

Before radio, letters were used to create fictional realities and storyworlds. Put together as a collection of action stories written in letter-form they become epistolary novels. Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719)3) is an example of an epistolary novel – a story presented as a ’real’ diary of someone stranded on an island, using his letters as a narrative device. Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740)4) is another example of an epistolary novel. It was so popular that people went to public squares to read the story to each other (as the majority of the followers was illiterate). Whole neighbourhoods would get involved, including the church, which would ring the bells at the end of the novel.

Aside from literature, ARGs draw heavily on theatre. Theatre games or improv are examples of some of the most rule-free ways of telling a story. In an improv the participants agree to share an illusion. Classic improv invites everyone involved to build on each other’s stories, but there is one rule that should be followed: you can never say no, always say ‘yes and…’. There is no direction, no outside force, just the imagination of a group of people working together. Theatre of the Oppressed5) is a well known example where improv is used to help communities deal with social issues.

More recently, the pre-history of ARGs includes role playing games (RPGs) and Dungeons and Dragons (D&D).6) In RPGs players take on roles of fictional characters in a fantasy world. A player is supposed to inhabit the character, where the character subsumes their own personality. D&D is a framework in which these games can take place: the player roles a dice to decide the outcome of their next move, which helps them tell a story. In D&D there is a predefined scenario with pre-made characters and setting. By limiting what you can do, the game frees you to imagine what you could do. Because of the strict game logic, collaboration is easier than in improv theatre. Your choices are up to you but only up to a limit, which helps prevent the paralysis of choice. Dungeon masters can move stories in different directions based on reactions of the players. Similarly, in ARGs puppet masters help the players get a more interesting experience. The point is not to win, but to tell an interesting story.

Board games are often neglected as a narrative platform, but they can be interesting places for stories to emerge. Board games are replayable stories about strategy and decision making, encouraging a playful narrative experience. Especially more collaborative games (such as The Settlers of Catan,7) Pandemic,8) or Space Alert9)) encourage storytelling through their appropriate mix of structure and flexibility. Battle Star Galactica10) is a mix of a competitive and a collaborative game; by being a game about how not to lose it is very successful at sustaining suspense and paranoia.

Online games (or massively multiplayer online role-playing games, MMORPGS11)) are an equally rich source of collaborative storytelling. For example, Eve Online12) has fascinating stories surrounding it, with real repercussions. The game has been going on for some years and the community intrigues keep expanding. If a new player would like to join the game, they have to go through a real-world interview to make sure that they are not spies.

Tarot readings are essentially a two-player storytelling experience. The card reader provides a broad framework, made out of pictures and words, the querent fills in their own interpretation and links it to their present and future. The mythic and archetypal structure of Tarot helps the querent grasp a universal story, identify with the Tarot archetypes and apply the story to their own lives. A very different example of fictional characters becoming a part of daily life is the Tamagochi.13) Tamagochi hype is perhaps not directly about storytelling, but it points to our ability to create (and experience) mass delusions, where people are willing to go quite far to maintain their beliefs about a fictional character needing their care and attention. A similar psychology can be found in climate change denials (i.e. cognitive dissonance), where stories are used to confabulate and justify people’s position and status quo in the world.

Finally, an example of participatory and alternate reality stories devised in the art world is the surrealists’ Exquisite Corpse,14) an associative method to build on one another’s words or images and assemble them collectively. Building on the idea of collective storytelling, Six to Start developed A Million Penguins,15) a wiki novel. The lesson learned through this experience was that a mere instruction to tell a story together is too broad, as it leaves people too much freedom and they end up not knowing what to do.

The past and present of alternate reality games: from marketing ploys, hoaxes and puzzles to context-specific experiences

ARGs appropriate and borrow from different media to create a transmedia story unfolding online and in physical spaces. According to Wikipedia, ‘an alternate reality game (ARG) is an interactive narrative that uses the real world as a platform and uses transmedia storytelling to deliver a story that may be altered by participants’ ideas or actions.’16) ARGs first emerged as an advertising tool for TV shows, movies, games and products. Early examples include The Beast,17) I Love Bees18) and The Lost Experience.

The Beast is considered to be the first ARG. It was designed as promotion for Steven Spielberg’s movie A.I. On the poster for the movie, ARG makers had hidden the name of an AI therapist. Curious fans could google him, find his website and a phone number. When they called this number, they could listen to the therapist’s voicemail, get passwords to access an email and the story would begin unfolding… The ARG became an expansive cross-platform story that could be found online and in real world events (such as an anti-robot protest). There was no mention that this was a movie or game.

The Beast can be considered a blueprint for ARGs (in the way it uses websites, phone calls, live events). It was also the first to use the TINAG (This Is Not a Game) aesthetic, where the aim is to suspend disbelief for as long as possible: never explain, never give players instructions, never admit what is real and what is fiction. In contrast, Electronic Arts designed Majestic: The ARG19) where it was obvious that it was a game (people had to pay for it). This game was much less popular than The Beast. Some games were real hoaxes, such as the marketing for The Blair Witch Project20) and Lonely Girl 15.21)

Most contemporary ARGs have stopped blurring boundaries between reality and fiction using TINAG, as this has alienated players in the past. According to Six to Start it might be best not to pretend that an ARG isn’t a game. Players prefer clarity about an ARG being a story. Puppet masters have a key role to play in providing this clarity, establishing trust in an ARG and making sure players’ participate but don’t get hurt.

In the last decade many new ARGS emerged, incorporating diverse contents and techniques. For example:

- 24 Alternate Reality Game22) is a post 9/11 quest.

- WWO or World without Oil23) included scenario planning and war drills, but no story.

- Lewis Hamilton: Secret Life24) featured a sports star as the main character, as a Robin Hood of fine art, retrieving stolen artefacts from thieves.

- Cathy’s Book25) was first released as a diary (a classic ARG ’rabbit hole’), mentioning a phone number; as players read the entries, they could find things hidden in the story.

- Perplex City26) sold its own puzzle cards as rabbit holes into the game, while the main story was told in blogs and fake newspapers. The fascinating aspect of this ARG was the community involvement. For example, players made a wiki, a formidable encyclopedia of everything that happened in Perplex City – there were about 1,000 editors, 1,200 pages, more than one million page views. On one occasion a puzzle demanded access to a library system. Players could access the system by becoming published authors, so they wrote, printed and published a book in two weeks, pointing to the importance of artefacts and live events to complement the online experience.

From The Beast to Perplex City it turned out that playing ARGs is very difficult and demands a lot of commitment. There was much disillusionment for a while, but then ARGs began gaining popularity again. In the last years there was a rise in period ARGs, often set in the near future (far future or past requires a lot of world building). The ARG for the TV series Lost (The Lost Experience27)) is an example that takes into account that people like dressing up and talking to each other. There are ARGs playing with alternate histories (what if…) and many ARGs about conspiracy theories – players understand how a conspiracy theory is supposed to work and are excited to get involved.

Over the years designers understood that the TINAG approach was perhaps not the best way to engage players; not knowing what it takes to play the game proved to be frustrating and alienating for many people. Nowadays ARGs have become more about context-specific personal experiences. Smart phones make it easier to contact the players wherever they are and adapt the story to their context and location. There is a large collection of location-based ARGs, ranging from a focus on gameplay to story generation and storytelling:

- Four Square28) is a location-based social networking site on which several monopoly-type games are designed using real locations.

- The street game Journey to the End of the Night29) is a grownup version of children’s chasing games like Cowboys and Indians or Hide and Seek.

- Tate Trumps30) is about telling stories using the known game mechanics of a simple card game, guiding visitors through the Tate Gallery in three ’modes’ (battle, mood, collector).

- Less about stories and more about playfully exploring the city is the location-based MMORPG Shadow Cities31) where a team of magicians fights against other teams. Using gesture-based casting of spells the game allows the players to transport themselves to a map of another city and work with their team remotely.

- Jane McGonigal’s Find the Future32) is a game about stories, storytelling and story-making that takes place in the New York public library, with QR codes hidden in books. By discovering the codes the players can find a task, then write a story. At the end of the game they made a book.

- The ARG Last Call Poker,33) designed to promote the video game Gun, is about playing poker with fictional ghosts and real people. Players are invited to visit graveyards and play the game based on years printed on real gravestones. Groups of people can play this game without any help from the creators.

- In Audi’s advertising game The Art of the Heist34) players were encouraged to learn about art by replicating a stolen painting.

- Wanderlust35) by Six to Start could be played on generic locations, such as a restaurant or a street corner, where the stories incorporated specific atmospheres and actions associated with these places (what we encounter in a restaurant is different than a library, or a street).

- A very different location-based cinematic experience are the Subtlemobs36) by Circumstance. They are story-based audio plays encouraging an intimate mass experience in urban locations, such as railway stations or markets.

- In Blast Theory’s Rider Spoke,37) stories are collected and heard by players on bikes. It is about connecting with people in an asynchronous way. Rider Spoke is not necessarily location-specific but is still location-based. It is about creating an emotional, personal experience.

- From walking and cycling to jogging: there is a whole genre of location-based running games that have emerged in recent years. Examples include Cache & Seek38) on Google Maps, where you trace your route and leave treasures for other joggers; Zombies, Run!39) by Six to Start, which adds a thrilling storytelling experience to your morning jog; and Seek ’n Spell,40) a jogging ’scrabble and boggle’ where the letters are scattered across the map and you run around to collect them.

Finally, it should be said that although ARGs are a good way to gather large communities around a cause, there are not many social commentary ARGs, i.e. games that make a point. Most ARGs promote causes that other people don’t disagree with and there aren’t enough ARGs that rock the boat, primarily due to issues of funding. One of the exceptions is America 2049,41) one of the more controversial ARGs, a cross between a Facebook game and an ARG about immigration from an ideological perspective.

An important thing to remember is that even if the game is about an ethical issue, it shouldn’t pass judgement on the player, but instead spark moral discussions – such as the game Fallout 342) about the slave society in Pittsburg. In this game the players were asked to commit morally questionable acts, such as murdering an infant in order to develop a cure for the whole population. This is interesting from a social perspective, as one player is not making decisions in isolation, but there are usually a lot of debates and conversations in the players’ community.

The palette of an ARG designer

An ARG has three arenas through which the story can develop: the real world, the online world and the ’transmedia’ world that connects the two. The online world uses the (micro)blogs, wikis, forums, IM, email, social networks and any other platforms where people communicate and tell each other stories. For ARGs the interesting thing is spreading the content across different digital, as well as physical and augmented platforms.

Today most movies are accompanied by books, toys, ARGs, online games and other merchandise, allowing the story to be told across platforms. The issue with such transmedia storytelling is that the user experience varies in quality. Every time there is a jump to a different medium, there is a danger of losing audience members. It’s good to be mindful of what the designers expect the players to do in a game, then design ways to keep them updated and engaged across different media. A problematic example is a Vook43) or ’video book’. You read a book and at the end of each chapter there is a link to a video; you can type the link in your browser and watch the video. But, how many people want to move from reading a book to a browser to watch a video? If they decide not to do this, they might feel like they’re missing out.

Another issue with the transmedia space are the mobile augmented reality applications, whose system doesn’t really know what is around the players in the real world – it might send them deep into the ocean, or across a border without their passports. Furthermore, running around a city staring at a mobile phone can prove quite dangerous. Nevertheless, the link between the online and the physical worlds remains one of the more compelling and exciting aspects of ARGs.

The real world in ARGs is usually associated with live events (with props and actors), but there is much more that can be done, including location-based games and real world multiplayer games, as well as making physical goods. Location-based games44) are games where the story develops related to the players’ location. These games can include digital content (e.g. you travel to a location and your phone tells you a story) and/or physical content (e.g. you have to go somewhere to pick up a package). Location-based games are just one of many possible multiplayer games that can be played in the real world. They range from party games to urban games (treasure hunts, scavenger hunts, meetups) and support the ARG community’s love for getting together and talking.

Physical goods include things such as books, letters and artefacts – objects deeply related to the story. ARG designers make them, but the players do it too. Here is where the world of ARGs meets maker cultures. Socks Incorporated45) is a great example: people create their own sock puppets and share them online. Many people enjoy crafting and making stuff. Nowadays it is becoming easier to design, make and share things using services as Shapeways,46) Reprap47) and Fablabs,48) Moo49) or The Newspaper Club.50) It is rare to lose players by suggesting they make something, even though some people wouldn’t do it themselves. This aspect of ARGs is all about nice gestures and small rewards. Furthermore, physical objects can become a good revenue stream.

Live events require quite a bit of effort and resources. They have a specific time, place and duration, similar to flashmobs.51) Live events get most press, but are expensive and difficult to set up. The audience in a live event is limited (hundreds rather than thousands), but the effect is strong: it locks the ’hard-core’ audience into the story and achieves more commitment. The weirder or more fantastical an event is, the more people get into it. Events should be designed like LARPS (live action role playing games)52) – where everyone can get involved and become a part of the story. Live events are a good tool in the arsenal, but not the only thing to focus on. One of the issues with live events is that they are places where the two different worlds collide (online and physical) and there is often a confusion of boundaries and issues with the ’fourth wall’:53) People don’t know how to behave, as there is no standard formula. There is much to learn from experiential theatre companies about managing audience members in live events.

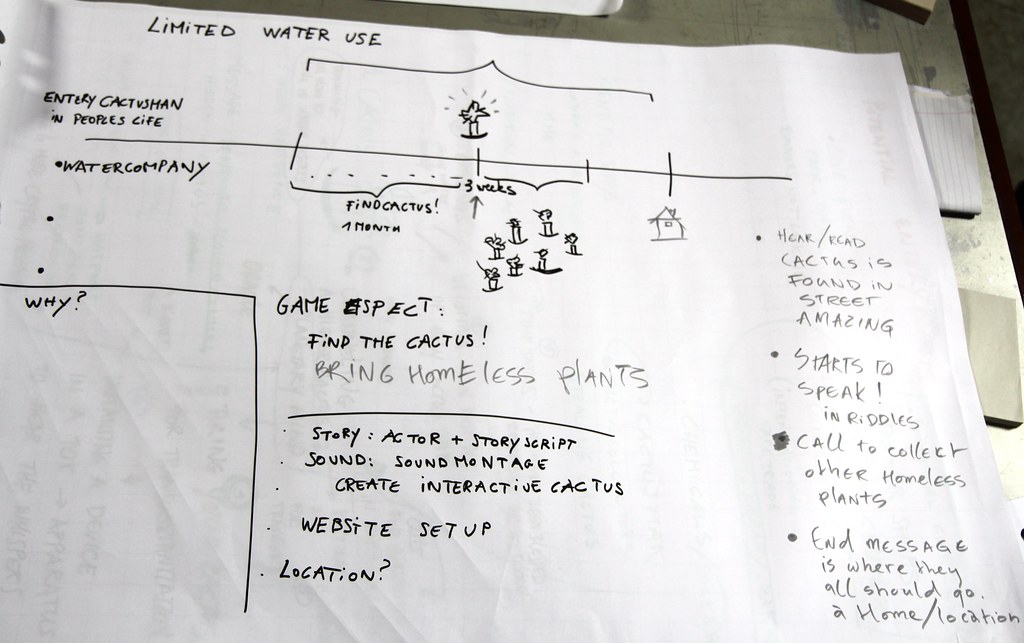

As the previous paragraphs show, when beginning to design an ARG there are many possible avenues to follow. Having so much potential gets novice designers overly excited and they tend to try to do everything in one game. It’s good to remember that limiting yourself brings out more of the story. An ARG is a complex system of multiple media, spaces and people, so good coordination and record keeping is essential. A good way to limit the possibilities is to look at the skills of the people around you and making a priority of things that they can do: if for example your team primarily includes people who can make websites, focus your ARG on the online storytelling rather than live events. Throughout the design process keep asking yourself – why? Why play? Does this make sense? Would I do it? Even creating great ARGs begins with yourself.

Telling a story or creating stories: on complexity of sense-making in ARGs

ARGs are successful when they tell their story in a way that we’re used to finding out about our world – when their narratives fit into the rhythms of our lives. Most ARGs have phone numbers and voicemails, blogs and websites; many are filled with puzzles. Puzzles are a very common mechanism to engage players in the story, but they tend to eat up a lot of the content and are not commonly used in our daily life to find out about the world around us.

Successful ARGs include a good dose of community building. An ARG community likes to have their own space where to discuss things, organise and share information, such as a forum or a wiki. If one isn’t provided with the game, players might create their own (this can create additional commitment). Lostpedia54) is a good example of a wiki built by the players of The Lost Experience, where over time disparate players became an active community. Facebook is another place where people like to talk about things. The problem with writing stories on Facebook is the scattered nature of conversations that challenge the chronological order and legibility of the story. There are some parallels between story generation in ARGs and open source software: there is a large volunteer base, but the question is how to maintain the artistic coherence when so many people write and rewrite stories.

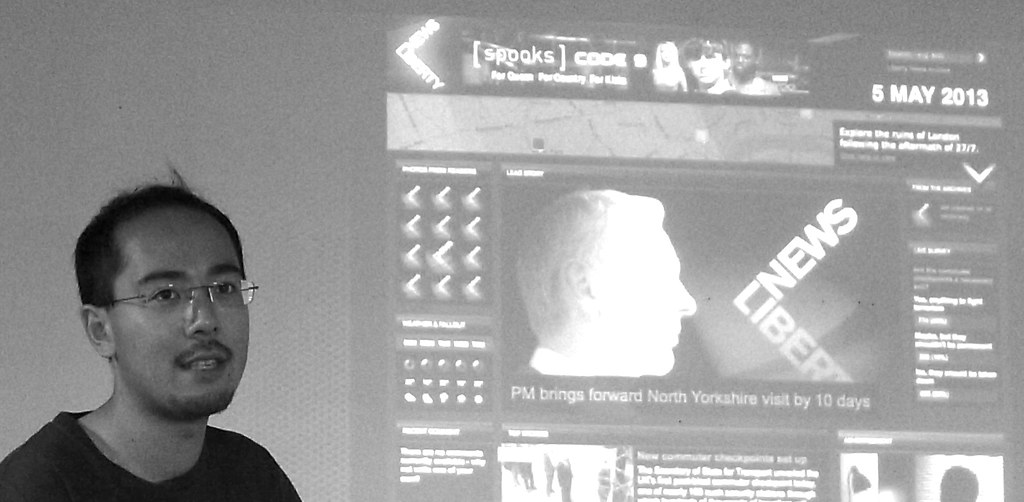

The complexity of the narrative is related to the communities’ ability to piece things together. If it’s too complicated, people lose interest quickly. Each story-fragment should be entertaining and interesting in and of itself. In Liberty News,55) the ARG accompanying the TV series Spooks Code 9, Six to Start designed a news site with comments, including a live chat with ’the prime-minister’s office’. Live Q&A sessions kept the story fresh and the players engaged. Another Six to Start ARG that included many mysterious, scattered story fragments and clues was The Code56) treasure hunt, released as a puzzle book accompanying the BBC documentary series about mathematics. Both these ARGs were designed to include sufficient granularity: single ’seeds’ or episodes for the casual viewers and a deeper storyworld for the ’hard-core’ fans.

The majority of the ARG audience are casual participants. They don’t want to make long-term commitments. If the game is based on mandatory interactions, there is a risk of losing many audience members. Players like to have an illusion of being able to make choices, but most of them just want a good story. In online fantasy games the players’ choices impact their ending. Choices can remove a lot of subtlety from the story, thereby creating many options, but the plots and characters can become black-and white or one-dimensional. When the story is forked, more content needs to be generated. If it’s a story with just one ending, as in a lot of games, this allows for creating multiple perspectives on the same narrative.

The important question to ask when making an ARG is: are you telling a story that is exciting to be told, or a story you want to construct together with the players? The first job (of both designers and players) in an ARG is to assemble the information and make sense out of it, to understand the scope of the problem. Too much ’and-and-and’ in an ARG can be dangerous. As Brenda Laurel writes in ‘Computers as Theatre’:57)

‘The number of new possibilities introduced falls off radically as the play progresses. Every moment of the enactment affects those possibilities, eliminating some and making some more probable than others… At the final moment of a play…all of the competing lines of probability are eliminated except one, and that is the final outcome… Thus, over time, dramatic potential is formulated into possibility, probability and necessity.’

Why make an ARG?

Making stories about alternate realities is an idea that won’t die. With ARGs we can experiment with different ways of telling these stories across physical and online worlds. The stories in ARGs are told in familiar ways, akin to the way we learn about the world our daily life. Players can become engaged in an alternate reality of an ARG while remaining themselves. As ARGs encourage us to discover and explore the real world while being immersed in a fictional reality, they make us think about ourselves and how we engage with others. By doing this, ARGs have the potential to bring large communities together to experience, generate and tell stories. In their community-building capacity, ARGs are different from entertainment and literature. They are a new medium in its infancy, with its screen being the entire world.